If there is a truism about the oil business, it is that oil companies – not contractors, not suppliers nor service companies – always make money. Any time an oil company announces a loss, it is rarely a real loss, only a bit of paper shuffling, asset write-down or expenditure write-off. If bp – notice the lower case letters used now which are meant to downplay its size and significance – could survive the $40bn plus cost of the Deepwater Horizon/Macondo catastrophe, then assuredly any operating company can always make money.

The question is how much money? Should it be unlimited, concomitant with the risks associated with the business? Or should there some limitation based on the importance of energy to the world’s population? A serious question that should not be downplayed.

Let’s start with risk. There has always been oilfield risk, usually associated with exploration drilling. For example, two of the biggest energy companies – ExxonMobil and TotalEnergies – drilled around the rim of the giant Johan Sverdrup field in Norway without finding this enormous resource. It took some geoscience nerds who worked for Lundin Energy to come up with a different geological model of the structure and find the resource. So ExMob and TotalE spent millions drilling and finding nothing, except they got to write off those expenses. Not the worst scenario. Another example from outside the oilpatch is Cocoa-Cola. Nearly 40 years, some genius at Coke decided that the way to stem its loss of market share to Pepsi was to come up with a new formulation, dubbed ‘new Coke’ or ‘Coke II’. Unfortunately pre-launch testing of the product showed that its faithful drinkers didn’t much like the new taste and petitioned the company to return to the old recipe. Of course, in 2022, this would have happened instantly on social media. Anyway Coke’s risk was at least mitigated by its ability to backtrack to its old formulation. But it must have cost it millions, not only to discard the new version, packaging, et al, but also in the loss of faith with its customers.

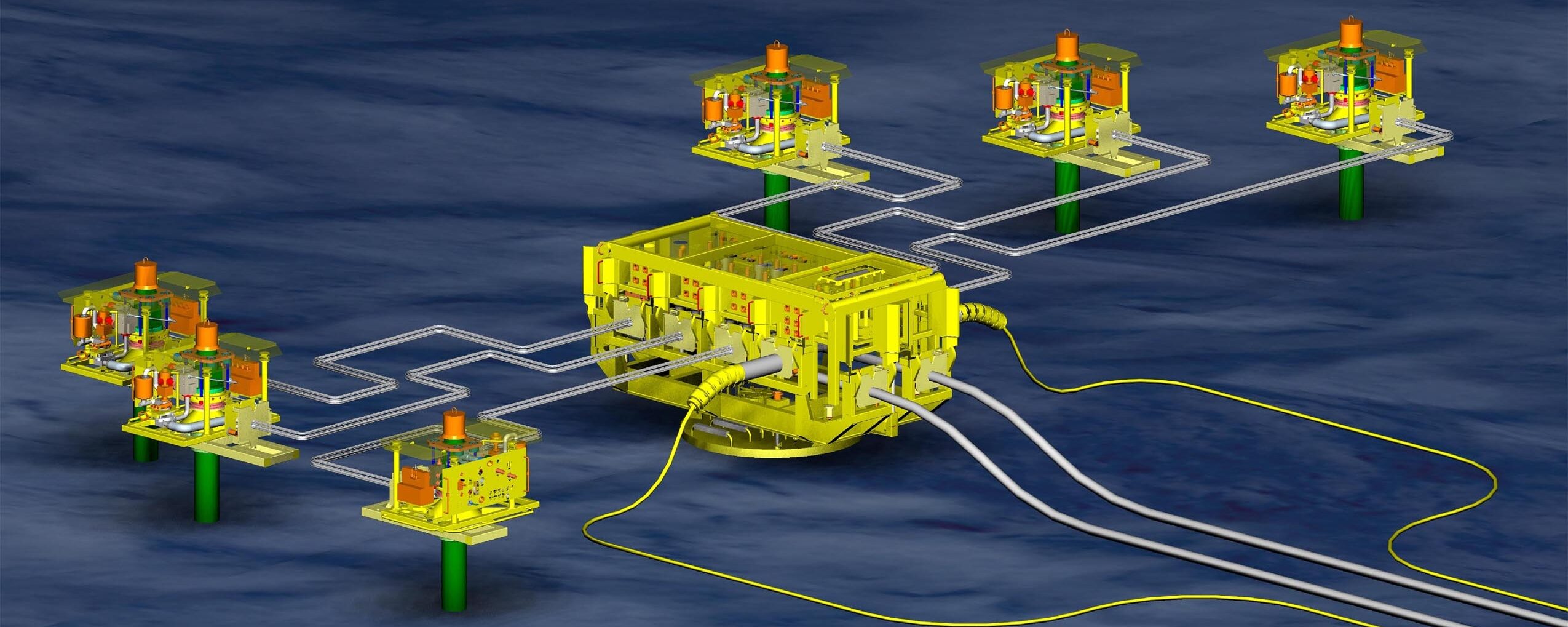

When oilfield development costs started to get out of control in the last two decades, the oil companies decided that they should dump risks onto the contractors. Bad idea. At least one of the big contractors nearly went under trying to handle the risk which would have put a serious damper on big West African and Gulf of Mexico deepwater developments. Eventually the operators had to discard this model for contractors or else there might not have been any left. But they tried. So they don’t much like risk, even if it is the basis on the industry.

And now for profit limits. When I was growing up in New York in the 1950-1970’s, the big electricity generator Con-Ed was not allowed to raise the price of electricity without going to a public hearing and prove to NY state regulators that a price rise was justified. I believe that Con-Ed was allowed a 10% profit on capital expenditure, quite a bit lower than the 15% RoR that operators used to work to. So the ‘private enterprise with a profit limitation’ model has already existed. This what the Conservative government in the 1980’s forgot to add in when they privatised the gas and electricity markets in the UK. It is unlikely that we will see such profit limitation instituted here, but the windfall tax forced on the current UK government and now extended by several years is the only way to fund energy cost mitigation for the public without the country going totally down the tube which it might do anyway.

I bring these issues up because my favourite organisation (not!), OEUK, the body formerly known as Oil & Gas UK, continues to cry for the government to help out the poor unfortunate oil companies who are having to reduce their profits that they did nothing to earn when the prices of oil and gas spiked due to Russia’s unjustified war in the Ukraine. Sorry but no sympathy from here as my office is cold as I watch the electricity meter run amok.