Few folks outside of the world of hacks know how we go about getting the news that everyone wants to read. Up until the year 2000, everything was copacetic – a lovely word that means absolutely nothing, but infers that all is well. Journalists like me had a Rollodex – remember those? – full of contacts gathered over more than the 15 years of plying the offshore beat and if someone asked me a question, if I did not know the answer, I always knew someone who did.

Then along came the Enron scandal and the business world in general – and the oil sector more specifically – changed so dramatically it is hard to remember what it was like before. From the investment community’s point of view, things got better. They no longer had to wait from one annual meeting to the next to know how ‘their’ company was spending its capital. They were now going to be told quarter by quarter. From the ‘company’ point of view, it meant that a good deal more resources had to be re-directed from doing ordinary communications, ie talking to specialised journalists, to producing all of the information required for those quarterly reports and talking even more to financial specialists. It also had to justify the vagaries of project spending. No way to gloss over short-term overspends which could have been relatively meaningless in terms of total project economics. And for us oilfield journos, there would be little time to answer project questions and no visits to see how operators were meeting some extraordinary technical challenges in project developments.

I bring these points up, because the challenges of knowing what operators are doing these days has become increasingly difficult. Not impossible if one has the time to trawl through quarterly reports and the occasional operational updates and glean tidbits from them. To wit, I give you last week’s offering from EnQuest. So what did we learn? Some of the background was not new, such as that on the Dunlin bypass project to re-direct production from the Brent Export System into the Magnus system and on the wax deposition problems at the Scolty/Crathes infield pipeline, but interesting nonetheless. As mentioned back in my first blog, the industry seems not to have learned much about flow assurance over the last two and a half decades and it might be time for operators to use more than a beakerful of oil from a production test when deciding on the design parameters for developments.

What was of more interest was the passing mention of issues with downhole pumps. At Alma/Galia, onstream since late 2015, EnQ is replacing a trio of electric submersible pumps (esps), possibly the most unreliable piece of equipment in use in the oilfield. Hey, maybe this was a good run for those esps or more likely they were being replace for second, third or even fourth time. It is really amazing that no company has been able to find a way to make esps more reliable, but this is an old issue. Over at Kraken, where EnQ has chosen to use hydraulic submersible pumps (hsps), developed by Weir and first used by Chevron at Captain more than two decades ago, there have been problems not with the pumps themselves put with the power generation system which had reduced the operability of the topside water pumps which provide the drive for the hsps. If it is not one thing, it is another!

Anyway the object of this exercise was to point out how difficult it is now, compared to 20 years ago, to report comprehensively on what is going on in the industry. In the ‘old days’, there were folks like Charlie Shepherd of Phillips, later ConocoPhillips, who really liked talking to technical hacks about what they were doing. Not much of that now.

***************************************************************************************

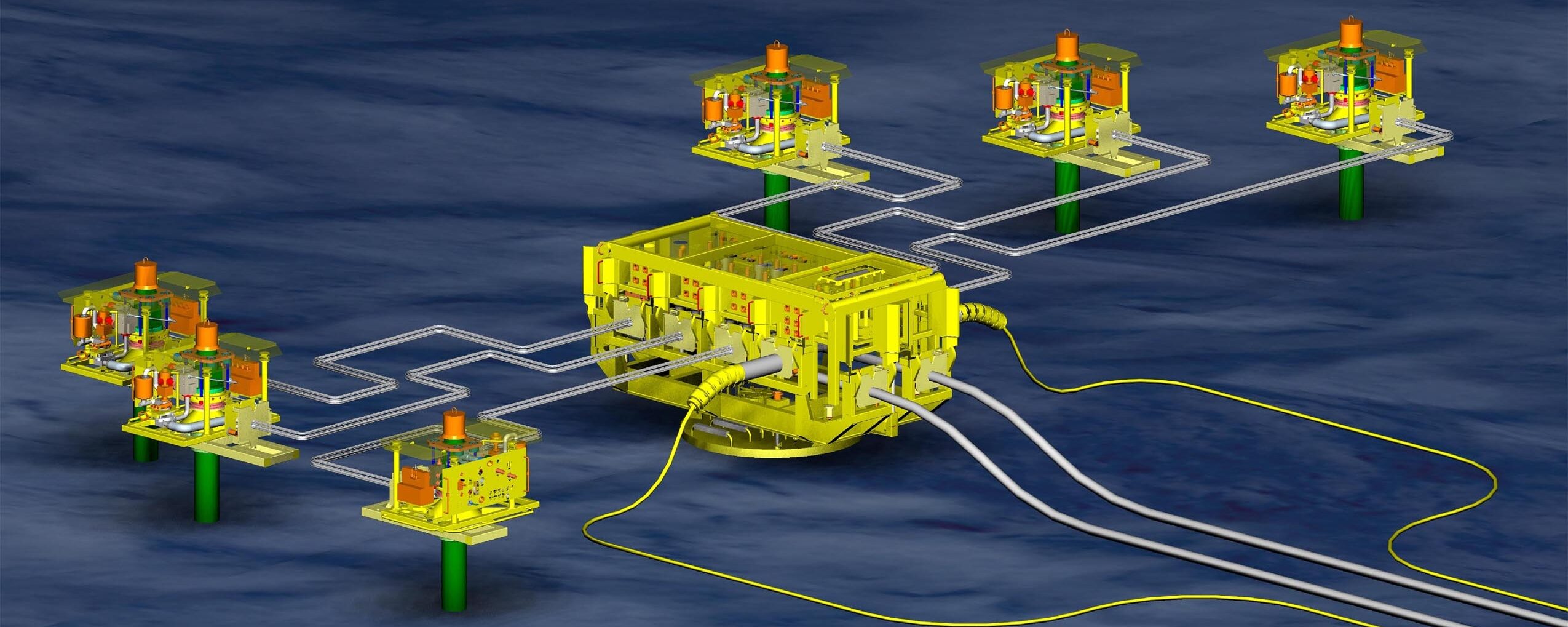

While on the subject of technology – what else? – the UK’s Oil & Gas Authority released details of its Energy Portal’s list of new and emerging technologies. And of course, I focused in on the subsea sector. I really wish that I could say that it made me go ‘wow’, but it did not. Some of the technologies are not new, some of them are quite old and some have been awaiting deployment for years, but that is another old offshore tale.

So what’s old? Subsea multiphase meters, pipeline drag reducers, electric heating for pipeline for flow assurance purposes, multiphase pumping, subsea processing and others. It may well be that some of the newer operators are looking for a bit more competition in the marketplace, but don’t try to say that any of these technologies are new. What did catch my eye was that one of the newbie operators, Siccar Point Energy, has its fingers in a number of initiatives involving these so-called new technologies for its assets west of Shetlands.

While Siccar is new, its management is not, several of its key people having been involved with companies which have done floating and subsea projects both as operators (Venture Production and Centrica) and on the contracting side (CSL). So why they are trying to re-invent the wheel is beyond me.

Among the untested technologies are alternative local energy sources and local chemical injection. The latter would go hand in hand with all electric controls and slimmer umbilicals which would require downhole chemicals to be stored on the seabed. Even the former is not actually new. I remember work done at a number of British universities on creating energy through electrolysis of seawater with battery storage. And if I recall correctly, a certain historical subsea system in the Gulf of Mexico back in the 1970’s had a nuclear power source.

I have to admit, though, that the idea of using a wave or current device to produce power for a subsea system does pique my interest. Only how long will it take before someone gets it in the water for even a pilot project? I would love to see it happen, but I am not holding my breath.