I cried yesterday. I don’t cry very often. I didn’t cry when my mother died, even though I loved her dearly. She was 93 and waited until she saw me and my oldest son one last time and then moved on. I cried yesterday, unexpectedly, while watching the new three-part BBC documentary about the Piper Alpha offshore disaster in 1988. It moved me so.

I was just four years into my editorship of Subsea Engineering News when the Piper Alpha accident occurred, but I was no young callow journalist. Fourteen years earlier, on my first day on my first job working on a weekly newspaper on Long Island, just outside New York City, I was sent to the scene of an accident where a young man, in the throes of a drug-induced stupor, wandered over a level crossing and was struck by a train. When I arrived there, the train was somewhat in the distance, the body was covered with a sheet, but his arm was sticking out over the rail. I got that photo. I was the only one with that photo. It is not that I was callous. I was there to do a job. I did it.

As the editor of a specialty technical publication, my job, in the aftermath of the Piper Alpha tragedy, was to ask the questions: why did this happen, should it have happened and how can the industry prevent it ever happening again? Sometimes one benefits from other people’s horrors. I was asked to write an article for The Times of London on how it would be possible to put out the fiery wells half a week after the explosions. I was asked to do BBC Breakfast TV and to do the BBC daytime radio news programme The World At One. It was the highest profile my publication and I would ever have with the general public.

And yet, there is a number that would put the entire event in perspective and which I will never forget: 167. That was the number of people – I guess mostly and probably all men – who lost their lives that evening. It is not that I didn’t care about the deaths. Of course I did. But my job was not to speak to the survivors, their families and the families of the deceased. That was the job of the BBC, the Aberdeen Press & Journal, the Scotsman, the other Scottish newspapers and media and the national daily papers based in London. My job was different.

And not only did I do my job, but I was part of the solution. I organised the first technical event to discuss one of the key recommendations of the Cullen enquiry: how to establish a safety zone around the platform and prevent any future fires from being fed by an uncontrolled flow of gas. For those who are too young to remember this event, it was this gas that turned an offshore accident into a conflagration that would kill most of those workers. Piper Alpha was a waystation in a gas transmission system. When a riser bringing gas from the seabed across the platform ruptured, it would feed that first small fire. That riser was attached to a pipeline that was 23 miles long – I think that number is correct, but forgive me if I am off a mile or two – and filled with gas. Even if the platform at the other end has shut down the pipeline immediately, there would still have been 23 miles of gas to feed that fire. Almost impossible to imagine.

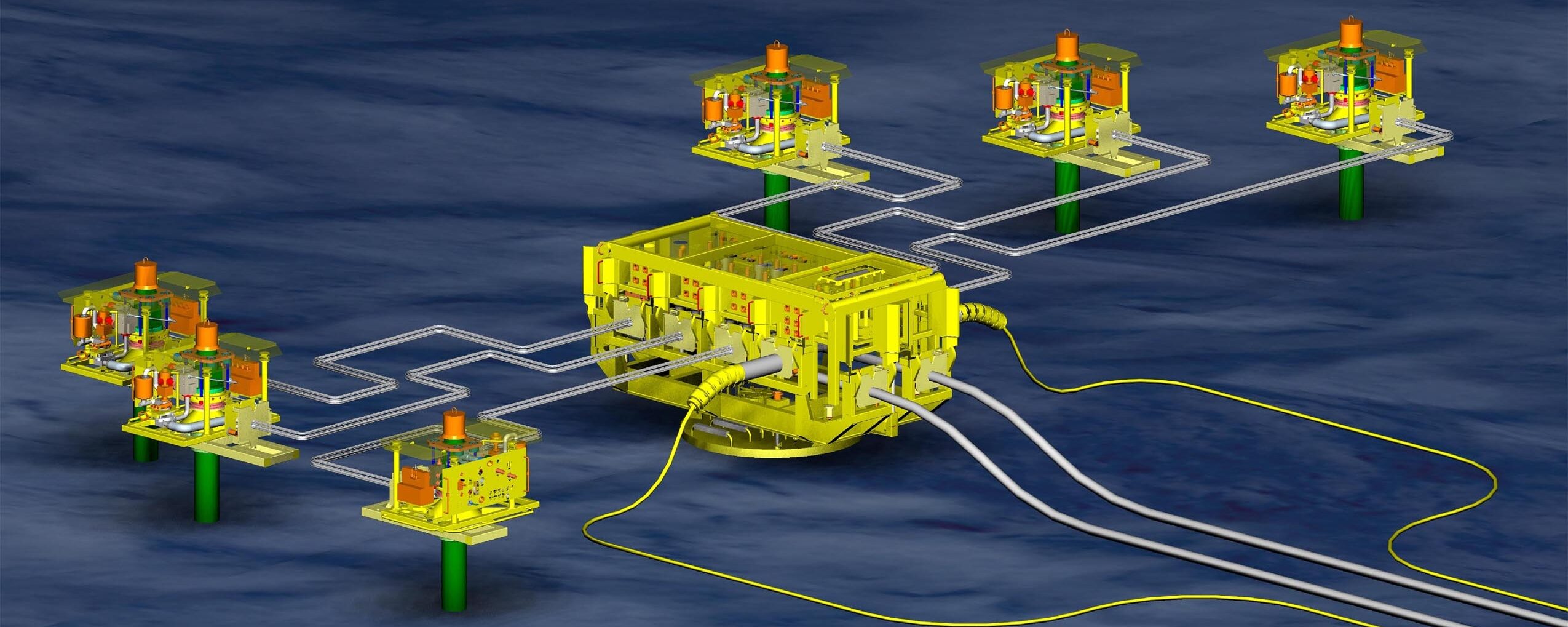

So in 1989, I organised a technical seminar on subsea emergency shutdown systems. Such a sub-system would not have prevented the initial explosion on the platform, but it would have limited the amount of gas that would have fed that fire. Such systems, when finally developed by some of the engineers who were at that first seminar, would be installed at every platform, 500m from its base, handling gas in the UK North Sea and beyond. I am proud of my involvement in that work.

And yet it did not prevent the deaths of those 167 offshore workers. Listening to the survivors talk about the traumatic events that led up to their escape from the platform, to families of those survivors and how they were psychologically damaged by their exposure to this event and to the families of the those who died and how their passing left gaps in the lives of so many people, was traumatic for me. There was a young man who was only months old when his father was killed. There was the wife and two daughters, then teenagers and now parents themselves, talking about the loss of their husband and father. There was the diving superintendent Ed Punchard who spoke so emotionally about the events of that night and afterwards. And the offshore work Bob Ballantyne who rescued a copy of Candide before he was able to flee the platform.

So I cried yesterday and my eyes are welling up now. It is difficult and probably impossible to put the events of that night out of one’s mind. Probably best not to try. Just cry if you must.